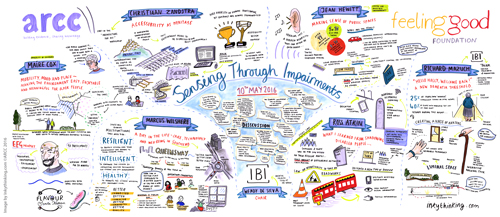

Our Feeling Good in Public Spaces dialogue series, run in conjunction with the Feeling Good Foundation, brought together researchers and practitioners to examine how people’s senses can be affected by the design of public spaces and building frontages, now and as our climate changes.

Good design for public spaces and buildings should not discriminate by age, gender, class or bodily ability. The fifth event of the series focused on how to design public spaces that empower people with sensory impairments, covering some of the less well-known sensory functions that aid our bodily perception of space.

The British Standards Institute (BSI) (2005) defines inclusive design as:

The design of mainstream products and/or services that are accessible to, and usable by, as many people as reasonably possible … without the need for special adaptation or specialised design.

Whether this or other definitions are used, it suggests that inclusive design is embodied as standard in the design process. However, the mainstream approach is to design additional tactics for what is considered to be a minority.

We are all likely to experience an impairment of some sort during our lives; as we age, we may develop either a visual or hearing impairment, as well as issues with physical mobility and balance. As the proportion of people over 75 years has increased by 89% since 1974, what was once a minority section of the UK population could well be the majority in the future, suggesting that designing for inclusivity is a vital part of future-proofing our public spaces. Although there is a wealth of guidance and policy that addresses accessible design, evidence from the series prompts the question: is policy comprehensive enough to ensure suitable life-course spaces for all, in the context of an aging population and a changing climate?

Ensuring a space is truly inclusive, in the BSI sense of the word, requires designers to look closely at people’s needs and expectations of a space. From a practitioners point of view, co-design – putting people at the heart of the design process – while acknowledged as a useful technique, in practice is far from straightforward. During the event discussions, practitioners expressed frustration with the tricky task of amassing representation from a whole community, and on the difficulties of engaging with people who are living with impairments, not all of whom will be known to housing, health or social services. For example, people with mental health issues are unlikely to get involved, or may need one-to-one engagement. Ascertaining the specific views of people with sensory impairments can be perceived to be catering for a minority, and the associated costs considered an additional expense.

The event discussions highlighted the contradictions between guidance on what is considered ‘good design’ and the seemingly negative impact this can have on people with sensory impairments:

- Street guidance that promotes shared space, designed to tackle traffic speed and the creation of a ‘sense of place’ can often make it difficult for people to process and understand how to use that environment. The use of mixed materials and patterns can create visual confusion, especially for people with visual impairments.

- The move to de-clutter streets by removing signage and street furniture, while on the one hand helping to remove obstacles, also creates problems for people who rely on the signage to navigate, or use the furniture to lean against and use as support.

- Secure-by-design guidance tends to remove opportunities for quiet spaces, seeing elements such as alleyways and door recesses as places that encourage crime. These spaces, if designed well, can offer quiet points for those suffering from auditory conditions to escape traffic noise.

- While there is general consensus on how the ‘car must no longer be king’ in cities, we must not forget that excluding cars also excludes people with impairments who rely on the car for mobility.

We should think critically about the impact of such contradictions, and find alternative design solutions that don’t have negative impacts; this means working across sectors to find solutions that work for all.

To create effective, inclusive design solutions, we need a truly holistic understanding of how humans function at a physiological and psychological level; how the senses interact and influence each other, and how they adapt to differing conditions and climates. The disconnect between evidence, practitioner knowledge, and policy needs to be rapidly closed before we can really claim to be designing healthy, inclusive, sustainable places.

A more detailed article on the event presentations and discussion is available from the Centre for Accessible Environments’ next ‘Access by Design’ journal, the UK’s leading quarterly publication on inclusive design.